How Queen Pu’abi and other royals got their servants for the afterlife at Ur

- Ryan Moorhen

- Dec 19, 2011

- 4 min read

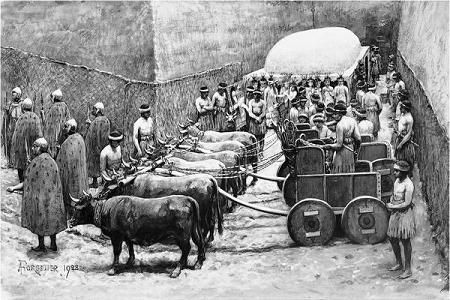

“During the burial of a king in the Royal Tombs of Ur, men and women were sacrificed to be the servants of royalty in the afterlife. They were arranged as shown, then they were given poison to drink.” (Source)

I originally wanted this to be one general post that covers tombs in Mesopotamia, but as I often find during my research, there is just too much to write about with due thoroughness in one post. So, in an attempt to give you my best for each of the two burial sites I wish to explore, this is post one of two that will explore the most interesting finds at two burial sites in Mesopotamia. It is pretty wild what those tombs have held for as much as 4,500 years…

When we think about extravagant burials and tombs, our brains are conditioned to immediately travel to Ancient Egypt, and mummy is the word.

But putting the mastery of preserving the dead for thousands of years aside, the Egyptians weren’t the only ones who buried their elite with extravagance, style, and cast curses over those who disturbed such tombs. The Mesopotamians liked to go out with a bang too, and their most interesting and prominent tombs of that nature happen to be those of elite women.

Burial tombs have been unearthed throughout Mesopotamia, dating to different periods and containing all sorts of artifacts that provide glimpses into the ancient civilizations that rose and fell in the land between the two rivers, and the fragile skeletons of those who were part of such civilizations.

I’ve talked about the Royal Tombs of Ur, or rather touched on them, when I talked about the Golden Lyre of Ur Project, but I barely scratched the surface of what happened when an important person died in the ancient Sumerian city.

You remember I talked about British archaeologist C. Leonard Woolley finding the Golden Lyre of Ur in Queen Pu’abi’s tomb? Well, he found a lot more than that during his excavations in Southern Iraq, between 1922 and 1934. What I did not tell you is that Woolley and his workmen found over 1,850 burials at the site, and 17 of those were so elaborate, Woolley dubbed them the Royal Tombs of Ur.

Most of the burials there date as far back as 2600 BC. They are tombs of the elite of society, those who played big roles at the temples and palaces of Ur. Still, of the 1,850 burials there, 137 were private tombs of those who were simply wealthy residents, able to afford a burial in the Royal Cemetery.

Queen Pu’abi’s headdress, made of gold, carnelian and lapis lazuli.

Queen Pu’abi’s tomb is the most prominent of the Royal Tombs, because of how well it was preserved over the centuries, thanks to looters leaving it be, a courtesy they did not extend to the other surrounding tombs.

We know the woman whose remains were found atop an elevated slab is Pu’abi, because of the cylinder seal found with her, which bears her name. There is much debate over who Pu’abi really is, whether she’s a queen or a priestess–no one knows for sure, but Pu’abi is believed to have been 40 years old at the time of her death, and that she was Akkadian. Her name in Akkadian is Pu’abi and translates to “Commander of the Father.” In Sumerian, she is known as Shubad.

Inside Queen Pu’abi’s tomb was not only her skeleton adorned with extravagant jewelry, including an elaborate headdress made of gold, lapis lazuli and carnelian, but also the skeletons of 26 attendants, also adorned with gold and lapis lazuli jewelry.

Woolley also found what he dubbed “The Great Death Pit,” which had 74 skeletons believed to be servants.

The site map of the Great Death Pit. You can click on the blue items and read further details about those items at the British Museum’s excellent website.

Woolley thought all the servants buried with their masters at Ur were willing victims, but later scholars have debated this notion and found ways to prove otherwise.

In early 2011, with the help of CT scanners and forensics, Penn Museum Archaeologist Aubrey Baadsgard and her colleagues did some sleuthing work to find out what really happened to the sacrificial victims found in the Royal Tombs of Ur.

Baadsgard and her team analyzed six skulls taken from different royal tombs and what she and her team found was quite chilling. Results, published in the journal Antiquity, revealed that these individuals died of blunt force trauma, blowing Woolley’s idea that these people simply drank poison and lied down to die in peace right out of the water. The results revealed that these people were dealt lethal blows to the back of the head by what appears to be a bronze battle axe in some cases, the like of which was unearthed at Ur.

And if that’s not a wow-inducing find by itself, then what Baardsgard and her team found next should do the trick. The bodies of these sacrificial victims had been embalmed for preservation with mercury sulphide or cinnabar, and further treated by heat.

Baadsgard’s team interprets this find of body preservation as an indication of an even more elaborate ritual for the burial of royals at Ur than originally thought. The need to preserve these bodies, the Penn Museum team concluded, was to cater to schedule of elaborate pre-burial ceremonies and rituals that could’ve taken days to complete, causing untreated corpses to decompose. You can read in more detail about Baadsgard’s amazing findings here.

And it seems that that, Ladies and Gentlemen, is how Queen Pu’abi and the other individuals who were laid to rest in the Royal Tombs of Ur got their servants to serve them in the afterlife.

Stay tuned for another set of tombs that are sure to make you shiver with excitement very soon!

(There has been a correction made to this article regarding the number of attendants found in Queen Pu’abi’s tomb. Please note that 26 attendants were found with her and not 74 as I originally wrote. Thank you, Jerald Starr.)

Sources:

Comentarios